BROOKLYN PARK, Minn.—Today, Matthew Ellickson admits it unprompted: When he was a teenager, he goofed off in school. He didn’t think he could make it into a four-year degree program.

“I started going to the tech school because I figured, ‘You know what? I’m not a very smart kid, I didn’t get good grades. Maybe I can go to a tech school and get a vocational degree.’ It really opened my eyes up to the fact that I could succeed in college. I did really well in that school, and I built my confidence up from there and my experience and education in an industry, and it opened my eyes up.”

That school was Hennepin Technical College, in this northern suburb of Minneapolis. The gateway to higher education that Ellickson found there was the school’s plastics engineering technology program.

It was the first academic step in his climb toward the executive position he now holds at Boston Scientific. As director of process engineering at the company’s plant in nearby Arden Hills, it’s Ellickson’s job to supervise how new products are moved into production at the facility, which employs about 2,000.

For decades, the plastics industry has been big business around Minneapolis and St. Paul. Thousands work in plastics manufacturing there, with a concentration in firms that make medical devices and components. Historically, plastics manufacturing meant molding the material by one of two processes: injection or extrusion. (Injection molding pumps semi-liquid plastic into a mold so that it hardens into that shape. In extrusion molding, the plastic is forced through an opening and takes that shape—for example, a rod, hose, or tube.) Those methods still dominate, but these days many more complex processes are used. And for almost 50 years, the plastics engineering technology program at Hennepin Tech has grown right along with the industry.

The program has had strong, consistent support from the region’s plastics businesses. In return, the school has provided industry with a steady stream of highly trained workers. Hennepin Tech students can’t earn an associate degree dedicated to plastic technology. But they can meld a series of non-degree credentials into a framework of expertise strong enough to launch a good career in the industry.

“They decided that the plastics program wasn’t going to be just about injection molding or extrusion molding. It’s going to be about all of the processes. We ended up being the best-equipped plastics program in the United States, and probably at least in the top three today,” Ralph said.

STRONG INDUSTRY SUPPORT

That support from industry has never wavered. Hennepin Tech’s cooperation with plastics manufacturers ensures that students’ learning stays relevant—and marketable.

At Hennepin Tech, a student who earns one certificate automatically gets a head start toward another. Suppose a student earns an injection-molding occupational certificate with five classes totaling 18 credit hours. With that year of part-time school, he or she has gained certified expertise ranging from the chemistry of plastics to quality control. Follow up with three classes (12 hours), and the student can add an occupational certificate in extrusion molding to the portfolio. That makes 30 credit hours, only six hours short of the most demanding certificate available in the program, called a diploma.

For years, representatives of the plastics industry have been on an advisory board maintained by the plastics program. About half of the board’s 22 members work in the plastics business. They use their direct knowledge of business trends to help guide the development of courses and certificates. In return, that helps the school maintain a 100 percent job-placement rate for graduates of the program.

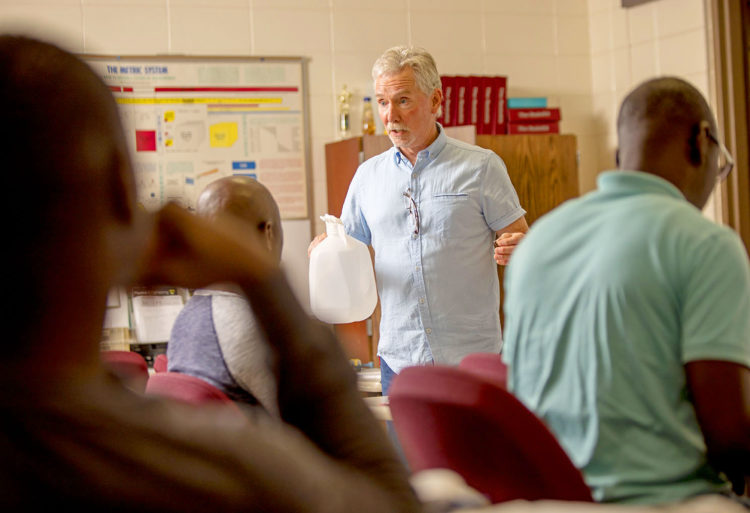

The number of graduates—24 earned a credential of some kind in the 2017-2018 school year—still falls far short of demand in the business, according to Dennis McNevin, an advisory board member and another early ’70s graduate of Hennepin’s plastics program. For years, he’s sold manufacturing equipment to plastics companies.

“That’s probably the single biggest complaint of any of my customers, is not being able to find the talent that they’re looking for,” McNevin said.

Ellickson discovered that demand 24 years ago as a student in the program. In 1995, while still attending Hennepin, he was hired as a production supervisor at Boston Scientific. It didn’t take long for him and his classmates to see the program’s potential benefits. “Every week, we’d have new postings up for new jobs at different companies,” he recalled. “It gave you a lot of exposure to the industry and opened up a ton of possibilities for people.”

Those plastics manufacturers attract many workers among the more than 200,000 immigrants who live in the region, many welcomed to the Twin Cities area through its long tradition of refugee resettlement. Many students in the program are immigrants, too.

Steward Sirueri, 32, is a good example. He won an immigration lottery in 2016 and moved from his native Kenya to the Twin Cities. Three years ago in Kenya, he and his family lived in an apartment, and they shared a bathroom with the tenants of several other units. They had never owned an automobile. On a good day, he made about $60 from operating a cyber cafe and repairing computers. Now he drives a Buick Enclave. His family’s apartment has its own bathroom and shower. His wife, Edina, 27, is an assembler at Teleflex, which also makes medical equipment. All told, it’s a much better life for Sirueri and his young family.

“The income is steady, unlike back home,” he said. “Over here, I can say it’s way better than at home.”

He works at Boston Scientific, in the company’s Maple Grove plant. He runs an extruder that makes medical-grade tubing.

“The first time I started working, I didn’t know what these parts were for. So when our supervisor told us that these are medical devices for hospitals, and they are used by human beings. … I like that I am making something which is going to be used somewhere, maybe to save life or improve life,” he said.

Ayub Sidow, 34, came to the United States in 2004 from Egypt. Sidow, who is from Somalia, spent four years in Egypt after his family fled violence in their home country. He’s worked for Proto Labs for 12 years. He took the advice of co-workers who told him that learning more about plastics at the college was the way to advance in the company. And he expects that the certificate he’s working on at Hennepin will give him an edge in earning promotions.

“I come to school because I want to move up for injection molding,” Sidow said. “One of my friends told me where he went to school and moved up to management. Gets more money.”

INTRIGUED BY THE DEFECTS

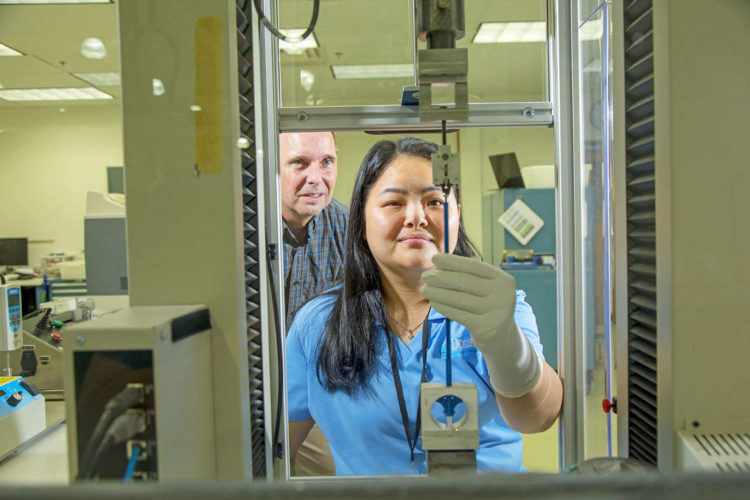

Muylang Aing, 34, came to the United States from Cambodia in 2005. Her work at Donatelle, which also makes medical devices, got her interested in the college’s plastics program.

When she started working in quality control at Donatelle, she was intrigued by patterns of defects she caught in pieces made by the company. “I was always concerned. What is that? Where do all those defects come from? How was this plastic strained? Why did it make this defect?” she said.

For example, she used to wonder about burns in plastic parts. “I always question myself, ‘What is it that caused that, the burn mark? … Why do we always get a burn mark on that plastic part?’ When I came here, I know (it’s) because of the gas leaking in the mold,” she said.

Not every student in the plastics program is an immigrant. Michael Thao, 23, didn’t get involved in the medical aspects of plastics manufacturing until he started working for TE Connectivity, a company based in Switzerland, with two facilities in the Twin Cities area.

“I started as an operator—working on a line, assembling parts, and then I moved my way up to braider, and then I went to the extrusion department,” he said. A braider is a machine that twists filaments together into a thicker strand.

“I only got interested in (learning more) after I moved into the extrusion department,” he said. “Hands-on dealing with medical tubings every day is just—every day’s a mystery. That’s what I like about my job. You come in, you have a new job to run.”

He’s confident that his education will set him up for a better career in the plastics business. “Education is power to you. … The more you have, that’s kind of like your skill set. Employers will look at that, and they would want to pay you a good amount of money to keep you,” Thao said.

The Hennepin program developed in step with the regional plastics business. Like many industry clusters, there’s no single, obvious reason that plastic manufacturers proliferate in the Twin Cities region. There’s a chicken-or-egg aspect to it: Many locals simply say it’s a great place to do business because there are a lot of plastic businesses here. Area firms train employees in similar processes and attract similar suppliers.

Treasa Springett, president at Donatelle, the company where Muylang Aing works, puts it this way: “Having a facility centrally located in the Twin Cities puts us in close proximity to some of the largest medical device manufacturers in the world. Engagements such as business reviews and technical meetings can be accomplished very efficiently,” she said.

The history of Donatelle illustrates how the plastics cluster grew. Springett said the company was founded in 1967 as a tool-and-die shop. It branched out into injection-molded plastics in 1979. By 1993, its work was so heavily concentrated in plastics that it changed its name to Donatelle Plastics Inc., she said. It now employs about 400 people.

Through a tuition-reimbursement program, Donatelle pays for Aing’s classes at Hennepin Tech, where she is in her third semester. Although the company recruits employees from many sources, Springett said that credentials from Hennepin are “certainly a plus.”

THE EQUIPMENT CONNECTION

The plastics industry helps the Hennepin program in another tangible way: It provides a steady flow of updated equipment through donations or loans. Many of these gifts are machines that would cost the school $100,000 or more apiece. And it isn’t just sentimental attachment that drives these donations, even though most are arranged by program alumni.

McNevin, who sells Toshiba injection molders, arranges for Toshiba to lend the program a new molder about every 18 months. “That benefits us, because when (students) get out in the industry, they’ve utilized some of our equipment. So a lot of times, they’ll end up calling me and asking me about possibly purchasing, too,” he said. The school’s production lab also provides a spacious showroom where prospective customers can see a tool in action, or where a company can train workers on a new tool before it arrives.

“The industry has been very supportive,” McNevin said. “It helps (businesses) if they can educate students to the degree that they need.”

And everybody needs plastic, as Ralph has been preaching for decades.

“The thing about plastics is, we affect every major manufacturing process in the world. So if it’s recreation, or construction, or electronics, we’re making plastic parts for every major manufacturer,” he said.

What plastics can really reshape, though, are the lives of students who find careers in the field. That’s the experience of Ellickson, the executive at Boston Scientific, and it’s the message he wants students to hear.

Since his first classes in making plastic, he’s earned a bachelor’s and three master’s degrees, including an MBA. He’s arranged the donation to the school of several expensive machines. And Ellickson frequently teaches a class at the college, supporting its mission with his own time and knowledge.

“I talk to my students in there now and say, ‘What are your aspirations?’ And they say, ‘Well, I just want to be a tech.’ And I say, ‘You go to this program, you start here, you are going to grow and achieve so much more than you ever thought you could have,’” he said.

Hard to argue with someone like Ellickson—an admitted teenage goof-off who used the program to mold an impressive professional life.