Worcester, Mass. – Quinsigamond Community College (QCC) student Kwame Ofori will present an impressive list of achievements on the transcript that will be sent to the Worcester State University admissions office along with his transfer application to begin classes there next fall.

His grades, good enough to earn Ofari a place on the QCC dean’s list, will be self-explanatory. And Ofari isn’t terribly worried that the transcript won’t point out that he earned those exemplary grades while holding down two part-time information technology jobs. But he is concerned that it will skip over his role as executive vice president of the QCC chapter of Phi Theta Kappa (PTK), the international honor society.

“A lot of people think we’re just into tech stuff,” he says. “This shows I can interact with other people.”

Absent a face-to-face interview, the Worcester State admissions team won’t find out that Kwami Ofari is, contrary to the stereotype of computer science majors, an extremely sociable young man. All they will glean from his official transcript are the courses he took during his four years at QCC, the number of hours he sat in QCC classrooms, the grades he received and his cumulative GPA.

Put another way, Worcester State will receive essentially the same document that has followed every Quinsigamond graduate since 1963, when the Boston-area community college opened its doors on the former site of Assumption College.

It’s because of students like Ofori that a QCC study team is now working to broaden its narrow record of students’ academic achievement. What they seek is a more comprehensive picture of the activities that shape students – in and out of class – and, most important, the learning that stems from those activities.

“I think it’s really important to show all the other activities you do because that is part of your college learning experience, says QCC student Cherise Connolly. “College isn’t just about grades and the classes you take. It’s about the whole, overall experience from all the other things you do, like community service – clubs that might not be academic, but might be just as important.” Connolly is wise beyond her years on this topic. She’s a dual-enrollment student, on schedule to earn an associate degree in business from QCC in May 2016, about a week before her graduation from nearby Shrewsbury High School.

The genesis of what Quinsigamond has dubbed the “co-curricular transcript” can be traced to a 2013 honors ceremony. At that event, which recognized QCC students’ participation in community service projects, Assistant Dean of Students Kevin Butler realized that Quinsigamond was doing little to formally acknowledge students’ volunteer work, employment-based learning and other non-classroom activities.

If QCC wasn’t keeping track of the extra stuff, Butler surmised, then it stood to reason that the four-year schools considering QCC transfers – not to mention area employers – had no clue what Quinsigamond students were accomplishing beyond the classroom.

“I thought to myself, ‘Are we tracking that information?’” Butler recalled. “How does one club know if a student is also involved in PTK and the theater club and the Student Senate? A lot of this info isn’t going on the official transcript. When a student transfers or (applies for) a job, we ought to be able to create something to give the student in paper form as a supplement to their resumé or transcript. And from there we started to have meetings to figure out what a co-curricular transcript should look like.”

At the time, Butler was unaware that decision-makers on other campuses were looking for ways to overhaul the traditional student record. “I had no idea,” he says. But QCC President Gail Carberry did. Never one to shy from innovation, she relished the chance to modernize the postsecondary transcript.

Room for improvement

“The truth is that kids graduate from high school with better transcripts than the transcripts they get when they graduate from college,” she says. “High school students have transcripts that show that they were on the football team or participated in certain clubs. And the reason they’ve done that for generations is because of the competitive process. The more you could show about your academic capability, as well as your well-roundedness, the better chance you had of getting into your college of choice.

Kevin Butler, QCC’s assistant dean of students, has been involved with the student record reform effort since 2013, when a ceremony to honor students’ volunteer efforts got him wondering: “Are we tracking that information?”

“Once they get into college we stop that practice. It becomes a numbers game. What it says is that you received 4.0 in one class and 3.5 in another. (It says) you did well in math, but didn’t do well in English. The transcript tells little about you as a human being. … And with all the opportunities we have to collect data and make it accessible to people (who make decisions), we should be able to use that technology in a meaningful way.”

Carberry encouraged a free exchange of ideas on the merits of expanding the transcript. Most QCC administrators have endorsed the idea of an enhanced student record.

Registrar Tara Fitzgerald-Jenkins, an administrator for 30 years, is among the dissenters. “Let’s not muck it up,” she says of the traditional transcript. “There’s value in it the way it is. I’m not sure we need all that extra stuff.”

The opinion of Fitzgerald-Jenkins notwithstanding, the revamping of the QCC co-curricular transcript is inching ahead. And to facilitate the process, Carberry turned to a pair of trusted advisers: Vice President for Strategic Enrollment Development and Student Engagement Lillian Ortiz, an administrator focused on the student side of the equation, and Dale Allen, vice president of community engagement.

Allen, a trained economist, is focused on connecting Quinsigamond students to the workforce and the world beyond. He draws on a parable to explain the process of overhauling the transcript. “It’s like approaching an elephant wearing a blindfold,” he says. “One person grabs the trunk and says, ‘It feels like a snake.’ Another hits the side of the body and says, ‘It feels like a wall.’ That’s where we are with this.”

For Ortiz, there is an obvious reason to address shortcomings in the student record. “We have over 40 student clubs on campus,” she points out. “The problem is students are graduating, seeking employment and not having all of their college experience recorded in one place. All of these students are very active and involved in the community. And it’s not showing up on their transcripts.”

A co-curricular transcript is a logical progression for a school led by a data-driven president who presses staff, faculty and students alike to “think entrepreneurially.”

“It’s an attractive target,” Allen says of the reformed transcript. But no one at QCC believes for a moment that hitting the bull’s-eye will be easy.

“We’re at a very rudimentary stage, and we are feeling our way through this,” Carberry acknowledges. “For us, very honestly, we need to find out from employers and the baccalaureate schools where we send our students what they want to know and how we can facilitate their selection process and what we can do to make (the transcript) more meaningful. Otherwise the transcript will be populated with a lot of nothing.”

Assessing ‘John Doe’

In late summer, a mock QCC transcript-of-the-future began circulating within the development team. The rough draft, on paper, is a relic of the pre-digital age. The finished product will adapt to the times.

“(Students) don’t want to deal with paper,” Allen says. “We need to be more adaptive to the technology that rules the way we do things today.”

The mock document – a co-curricular transcript prepared for “John Doe” – is essentially an addendum, something to supplement the fictional student’s official record. It testifies to Doe’s membership in the Chess Club, Student Senate, PTK and the Judicial Board; it shows that he volunteered at a pair of fundraisers, a bowl-a-thon and a charity cookout; it says he received “leadership training” at student government and PTK seminars and earned “service learning” credits in a Boys & Girls Club internship.

It also notes that Phi Theta Kappa honored Doe with a “Gold Stole Award.” But it doesn’t say what Doe did to merit the citation – or even explain the award’s significance. And it makes no attempt to identify actual learning outcomes – the specific knowledge, skills or abilities that Doe obtained or honed through this experience.

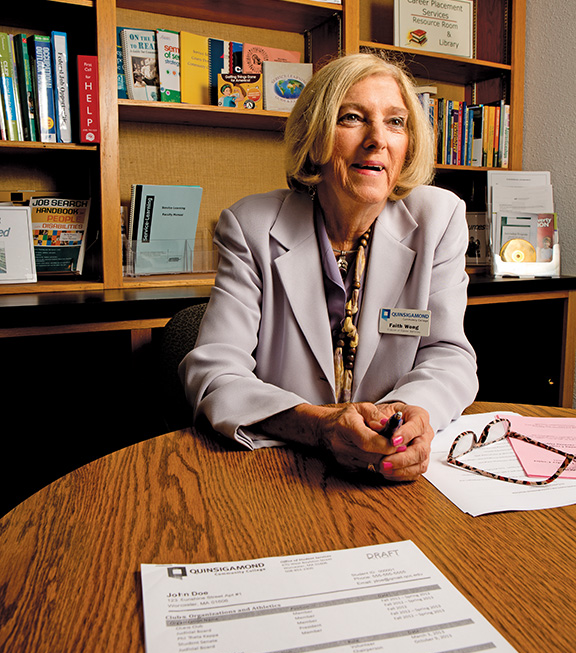

Director of Career Services Faith Wong, part of the transcript transition committee, admits that these shortcomings pose a problem. In fact, she says they represent “the perfect example of the work that needs to be done” to upgrade student records.

In the case of John Doe, she says PTK adviser Bonnie Coleman might be able to provide some answers. Correct. “The Gold Stole recipient means a student has done his Phi Theta Kappa community service,” Coleman explained.

Coleman has her own method of storing the recorded activity of PTK students. It’s called a file cabinet. It’s not that Coleman is technologically averse or digitally challenged (she backs up the information on a hard drive). It’s just that the current configuration of QCC technology makes it easier to keep records the old-fashioned way.

“A lot of students come back to me after three or four years to say, ‘I’m continuing my education; can you write me a letter of recommendation?’” Coleman says, pulling a file drawer open for inspection. “And I’m like, ‘Who are you?’ So we keep records of everything that is important in here.”

That process grows more cumbersome by the year. PTK had 30 members when Coleman took over in 2007, a number that has since swelled to more than 400. As membership has grown, so has number of projects, fundraisers and volunteer activities that must fit in the filing cabinet. And though the co-curricular transcript will make documentation easier, the logistics of implementing that system pose a different set of questions.

“Who’s in charge of (entering the information into the database)?” Coleman asks. “I would know if someone was on the basketball team. But if a student says: ‘I (volunteered) with Joe Schmoe,’ am I responsible for calling this person to verify that information?”

The answer to that question has already been determined: It will fall to each student to add to the record whatever information he or she sees fit. Students will be encouraged, as a hedge against memory lapses, to input information in real time, as it happens – a method encouraged by Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA – Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education.

“It needs to be an ongoing tool, not a summative tool,” says Kruger, a strong advocate of student record reform.

QCC has not yet determined how much information the transcript should convey to third parties. For instance, will it be enough to simply note that a student volunteered at a holiday party for underprivileged Worcester-area children? Or should the transcript include a link showing that the student baked and iced eight dozen Christmas tree cookies, dressed as an elf to distribute toys and afterward drove three families home in a blinding snowstorm?

Butler, the associate dean of students, believes QCC should take advantage of the technology and allow students to divulge as much information as they wish. He reasons that “a few clicks of the computer shouldn’t matter” to someone interested in seeing the full scope of a student’s commitment to service and learning.

Fitzgerald-Jenkins, however, fears information overload. “I do think there need to be some parameters or some order to it,” says the Quinsigamond registrar. “It’s one thing to know that a student worked in a soup kitchen. But do we need to know if he peeled the potatoes and washed the pots and pans?”

The verification issue

Determining the proper level of detail is clearly an issue that must be resolved, but it may seem a trivial one compared to the challenge of verifying all of those details. After all, even though students themselves are entering the data, that information doesn’t belong solely to them. In fact, the document that ultimately displays that information will technically remain the property of the institution.

That means Quinsigamond Community College will be accountable for the content shared with human resources professionals, four-year universities and graduate schools.

Fitzgerald-Jenkins points out that verification never posed a problem in the past. “If it’s on an academic transcript, then it’s verified,” the registrar says. “I believe students are honest. But not always.”

Carberry agrees that verification is vital – to students and to the institution. “It isn’t just developing the template around which we must insert information,” the QCC president says. “The validation of that (information) becomes a driver.”

As an example, she cites a multifaceted Phi Theta Kappa project to raise $100,000 for a bookmobile to promote youth literacy in low-income Worcester neighborhoods.

“There is student turnover during the course of the three-year project,” she explains. “We can document that they were part of the honors society that accomplished these goals. But how active each one of them has been? That’s not something we can capture at this point.”

In the case of the bookmobile project and most other activities, the task of verifying student-provided content will likely rest with the activity organizers and other adult leaders – club and organization advisers, coaches, and faculty members who integrate service-learning into their courses.

Carberry admits the new system may eventually add to faculty workload, though she says that hasn’t yet become an issue, even though QCC is in the midst of a hiring freeze necessitated by decreased enrollment. Cuts in state funding for higher education are also a consideration.

All of these factors keep QCC officials mindful that the effort to upgrade the transcript cannot occur in a vacuum.

Quinsigamond and a handful of other institutions are clearly at the forefront of transcript-reform movement. But its long-term effectiveness depends on the willingness of colleges large and small to embrace that movement.

“It’s expensive to do these plug-ins and improvements at any college, let alone across higher ed. And there’s a choice here,” says Allen. “The question is, if there are 20 things that need to be a part of all electronic transcripts in the future, how do we plug those 20 things into anybody’s system? I’d love to work with our friends on the digital side with that because our friends in the marketplace would be so much better because of it.”

Another, even larger, issue looms as well: How will the information contained in these new-look, digital transcripts – at whatever level of detail – convey what really matters? How will they demonstrate the specific knowledge and skills that a student has obtained or developed through the work described?

That knotty problem, perhaps the ultimate question in the student record reform effort, is a long way from being resolved. But work is certainly underway to formulate some answers (see DQP story on Page 18).

Much of this work is being driven by a job market that is increasingly hungry for ways to assess the intangible assets known as “soft skills”—communications proficiency, teamwork, leadership, and the like.

“A lot of what employers want today goes beyond academic competencies,” Allen says. “They want someone who knows how to be part of a team, knows how to show up on time, be presentable, and play well in the sandbox. We need to find a way for those things to show up in the (new) transcript.”

Solidifying the ‘soft skills’

Allen adds that students in certificate programs, particularly in the health, information technology and manufacturing fields, are “demanding and craving that (soft skills) show up on transcripts. And it’s just not happening. … All that shows up on our transcript today is that (a student) completed a three-credit course.”

It will take some time and more than a few adjustments, but Carberry believes Quinsigamond will emerge from the effort with an updated transcript that meets the needs of 21st-century students and employers.

“These are interesting times,” she says. “And in interesting times you have to move faster than you have in the past.”

You also have to face tough questions head-on. And Carberry herself poses a big one: “Are employers and four-year schools going to take the time, and will they be willing to assess a different, bigger, and stronger representation of students?” If so, she adds, “there is going to have to be a huge cultural shift as things are implemented. It has to start somewhere. Being at the front end has its risks. But it also has it rewards. Or at least we’re hoping so.”